In Romans 7 Paul expounds on his statement in Romans 6:14, “For sin shall not be master over you, for you are not under law, but under grace.” In 6:15-23, he used the analogy of slavery to show that we will not sin under grace because we have become enslaved to God and righteousness. In chapter 7, he explains what it means to be free from the law and how this relates to breaking free from sin’s tyranny.

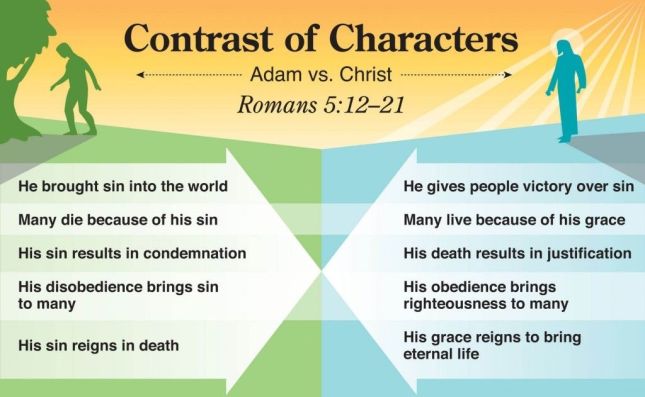

The theme in chapter 6 was sin; Paul uses that word 17 times there. In his mind, there was a direct correlation between sin and the law. In 1 Corinthians 15:56 he says, “The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law.” So there are several parallels between chapters 6 & 7 (Leon Morris, The Epistle to the Romans [Eerdmans/Apollos], p. 270): Believers have died to sin (6:2) and they have died to the law (7:4). We have been freed from sin (6:18, 22) and we are released from the law (7:6). We walk in newness of life (6:4) and we serve in newness of the Spirit (7:6). Our victory over sin is tied to our union with Christ in His death and resurrection (6:8-11). Our release from the law and its sin-arousing power is because we are now joined to the crucified and risen Lord (7:4).

So if we want to gain consistent victory over sin, we have to wrestle with Romans 7 as Paul explains the purpose of God’s law and our relationship to it. His thinking was radically opposed to the common Jewish views of his day. They would have said that the law was given to make us holy, but Paul says that the Law served to arouse us to sin! In chapters 1-5 Paul shows that it is impossible to be justified by keeping the law. Here he shows that it is impossible to be sanctified by keeping the law. In fact, Paul argues that the law is actually a hindrance to sanctification (Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Romans: The Law: Its Functions and Limits [Zondervan], p. 5).

The chapter falls into three sections. In 7:1-6, Paul shows that we are no longer married to the law. A death has taken place and now we are joined to Jesus Christ so that we might bear fruit for God. But that raises the question, “Then is the law sin?” Paul answers this in 7:7-12, showing that the law is holy and good. It is we who are the problem! When our sinful nature comes into contact with the law, it does not obey. Rather, it is aroused to sin. Then in 7:13-25, he shows the ensuing battle that sinners have with the law. This is a very difficult and controversial section, as debate rages over whether the person in view is an unbeliever or a believer. I do not want to raise your hopes that I will solve this puzzle for you, but we will try to work through it as best as we can.

In our text (7:1-6), Paul first makes a general statement about the law’s jurisdiction over a person as long as he lives (7:1). Then (7:2-3) he illustrates his point by showing that a woman is bound to her husband as long as he lives. He is not giving comprehensive teaching here about divorce and remarriage. Rather, he uses an analogy to make a point: the law has jurisdiction over the living, not over the dead. If a person dies, he is no longer under the law. Then (7:4), he applies the point, showing that we died to the law through the death of Christ. We are now “remarried” to Christ so that we might bear fruit for God. Then (7:5-6) Paul explains verse 4 negatively (7:5) and positively (7:6). We need to die to the law because it aroused our sinful passions to bear fruit for death (7:5). But in Christ we have been released from bondage to the law so that we serve God in newness of the Spirit (7:6). To summarize:

Through our union with Christ, we have died to the law so that we are free to bear fruit for God in the Spirit.

1. Through our union with Christ, we have died to the law, which only produced sin and death.

Many books have been written on what it means for us not to be under the law, so I can only give some brief guidelines here. I offer one negative and three positive thoughts to clarify what Paul means when he says that we died to the law.

A. Dying to the law does not mean that we are free from specific moral commandments.

We need to understand that we did not die to the law so that we could live lawlessly, doing whatever we please. That was the false charge that Paul’s enemies leveled against him. But Paul makes it very clear that we died to the law so that we might be joined to Christ, under His authority. Just as a woman is under the authority of her husband (according to the Bible), so we were under the authority of God’s law. But when we died to the law, it was not so that we could become free spirits. Rather, it was so that we could now be joined to Christ as our husband.

Paul’s analogy is rather confusing if you try to make it say more than he intends. In 7:2-3, the woman’s husband dies so that she is free to remarry. But in the application (7:4), it is not the husband that dies, but rather the wife dies to the law through Christ. By implication she is raised from the dead so that she can marry Christ, who died and was raised from the dead. But Paul does not intend this to be a tight allegory, where one thing consistently represents another. Rather, he is making the main point that by being identified with Christ in His death and resurrection, we died to the law so that we’re legally free to be joined to Christ.

But, dying to the law does not mean that we no longer are obligated to keep specific moral commandments. As Paul states later (Rom. 8:4), the requirement of the law is now fulfilled in us as we walk according to the Spirit. Sometimes it is argued that the only command under the new covenant is love, since love is the fulfillment of the law (Rom. 13:8, 10; Gal. 5:14). But this is often misapplied in a simplistic way so that “love” means whatever the person wants it to mean. For example, couples argue that it is okay to have sexual relations outside of marriage because they “love” one another. But the New Testament is abundantly clear that the sexual relationship is restricted to heterosexual marriage (1 Cor. 6:9-10, 18; 7:1-9; 1 Thess. 4:2-8). Love does not mean that we are free to disregard the Bible’s moral standards.

In fact, the New Testament gives many detailed commands about love. Love speaks the truth. Love does not steal, but rather labors so as to be able to give. Love speaks wholesome, edifying words. Love is not bitter or angry. Love is kind and forgiving. Love does not engage in immorality or greed (see Eph. 4:25-5:4). Many more specific commands on other topics are given throughout the New Testament to believers who have died to the law (see Romans 12). So we would be mistaken to think that dying to the law frees us from the obligation to obey specific moral commandments. So what does it mean?

B. Dying to the law means that we are free from the demands of the law as an impersonal system for approaching God.

While salvation has always been by grace through faith, not by works, many who were under the Mosaic law wrongly thought that they could be right with God by keeping the law. It was true: Keep the law perfectly and you will live (Matt. 19:17; Gal. 3:12). The problem is, that system brought everyone who tried to live by it under a curse, because no one could keep the law perfectly (Gal. 3:10). As a Pharisee, Paul thought that he was blameless with regard to the law (Phil. 3:6), but at best he was “blameless” only in the sense of outward obedience to the ceremonies and rituals that the law prescribed. The truth was that in his heart, he was proud of his blameless obedience, and pride is the root of all sins before God. When he met Christ, Paul came to see that he was actually the chief of sinners (1 Tim. 1:15).

So dying to the law means that we do not approach God by an impersonal system of performance, where we try to earn right standing with Him. That is the way of virtually every religion in the world, including many that go under the name of “Christian.” The good news is that God justifies sinners by grace through faith alone and that the core of saving faith is to know Jesus Christ (Rom. 4:5; Phil. 3:2-10). And, as I said, Paul’s point in Romans 7 is not only that we are justified by grace through faith alone, but also that we are sanctified in the same way (see Col. 2:6).

C. Dying to the law means that we are free from the condemnation of the law.

Paul says (Rom. 7:6) that the law held us in bondage. It did so by putting us under a curse because of our failure to obey it perfectly (Gal. 3:10). Peter refers to the law as “a yoke which neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear” (Acts 15:10). The law closes every mouth and makes us all accountable to God (Rom. 3:19). No one is able to be justified by keeping the law; rather, the law brings the knowledge of sin (Rom. 3:20) and puts us under God’s wrath (Rom. 4:15). The law increased our transgressions and held us under the reign of sin and death (Rom. 5:20-21). Attempting to be right with God by law-keeping is doomed to failure. The only benefit of the law with regard to salvation is that it shows us God’s impossible standard of holiness and thus drives us to Christ as our only hope, so that we will be justified by faith (Gal. 3:24).

D. Dying to the law means that we are free from the inability of the law to produce obedience.

This is Paul’s primary focus in Romans 7:5: “For while we were in the flesh, the sinful passions, which were aroused by the law, were at work in the members of our body to bear fruit for death.” In this context, being “in the flesh” means, before we were saved, before we received the Holy Spirit. As Thomas Schreiner puts it (The Law and Its Fulfillment [Baker], p. 133), “The law apart from the Spirit does not produce obedience. The law apart from the Spirit does not save but kills.”

Paul will explain this further in 7:7-11, where he says that coveting was not a problem until he read, “You shall not covet.” That commandment triggered something in him that made him covet all over the place. The problem was not with the law, which is holy, but with his sinful flesh. We can all relate to what he is saying. I wouldn’t think about walking on the grass if it weren’t for that annoying sign that says, “Do not walk on the grass.” The commandment makes me want to walk on the grass!

So the law is not the answer to our sin problem. Trying to keep the law can never reconcile us to the holy God, because we’ve all violated His law many times over. Posting a list of God’s commandments on the refrigerator and trying to keep them by our own strength won’t work, either, because the law just incites our sinful passions. It does not quench the desire to sin. The oldness of the letter was a “ministry of death” (2 Cor. 3:6, 7). We need a more powerful solution, which Paul gives in 7:4 & 6.

Paul says that we were “made to die to the law through the body of Christ” (7:4). That’s an unusual phrase, referring to Christ’s physical body. Paul is calling attention to the fact that in His human body, Jesus satisfied the demands of the law on our behalf, so that He “canceled out the certificate of debt consisting of decrees against us, which was hostile to us; and He has taken it out of the way, having nailed it to the cross” (Col. 2:14). So when Jesus died to the demands of the law, we died in Him. In summary, this means: We are free from the demands of the law as an impersonal system for approaching God. We are free from the condemnation of the law. The power of the law to arouse our sinful desires is broken, because being joined to Christ, we now have the Holy Spirit to give us the power to obey.

2. Having died to the law, we are now joined to Jesus Christ, which produces fruit for God in the Spirit.

As I said, God does not free us from the law so that we can live any way that we please. Rather, He frees us from the law (7:4) so that we “might be joined to another, to Him who was raised from the dead, that we might bear fruit for God.” Restating it in a slightly different way (7:6), this release from the law enables us to “serve in newness of the Spirit and not in oldness of the letter.” So our union with the risen Savior through the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit works in us to bear fruit for God. Note six things about this union or marriage to Christ:

A. Our union with Christ is a transforming relationship.

In verse 6, Paul uses the same contrast that we saw in 6:22, “But now.” It points to the great change from before we met Christ to afterwards. Before we met Him, we were in the flesh, enslaved to sin, and under the condemnation and power of the law. “But now we have been released from the law, having died to that by which we were bound” (7:6). If I have broken the law and am facing a prison term, but before I go to prison I die, they aren’t going to take my corpse to prison! My death released me from the power of the law. It changed everything.

Also, our death to the law freed us to be joined in marriage to the risen Christ (7:4). This implies that we have new life in Him, because Jesus doesn’t marry a corpse. We have a new relationship of love with our Bridegroom, who gave Himself on the cross to secure us as His bride. (By the way, it’s difficult as a guy to think of myself as “married” to Jesus, but think of it corporately, not individually. The biblical analogy is that the church corporately is the bride of Christ.) Our new union with Christ changes everything.

There is one thing certain about marriage: it changes you forever! Suddenly, you are not your own. You have to think about your wife before you make plans. You have to think about what pleases her. You have to take her into account in every decision that you make. You have to work at staying close in your relationship to her. But in spite of these new responsibilities, I can say with gusto that marrying Marla changed me for the good! In the same way, being joined to Jesus Christ changes everything. It gives you new responsibilities, but it transforms you decidedly for the good.

B. Our union with Christ is a love relationship.

As I said, the phrase “through the body of Christ” points to the cross, where Jesus died a horrible death to secure us as His bride. He paid the price that the law demanded for our sin. “Christ … loved the church and gave Himself up for her” (Eph. 5:25). So now we willingly submit to Him, not out of duty, but out of love.

Picture a woman married to a demanding, perfectionistic man. He’s the kind who takes a white glove and wipes it on the top of the door molding to see if it has been dusted. She lives in constant fear that she will not please him. But then (much to her relief) he dies. Sometime later, she meets a loving, kind, and caring man. They fall in love and get married. Now she still cleans the house and cooks the meals, but she does it joyfully out of love, not dutifully to meet the demands of an impossible tyrant.

The analogy breaks down, in that the law did not die. Rather, we died to it. But, we no longer have to strive in vain to meet its impossible demands as the grounds of our acceptance with God. Rather, Christ met those demands for us and we are joined to Him in love. We still live to please Him, but our whole motive has changed from duty that condemned us to love that accepts us.

C. Our union with Christ is a liberating relationship.

Before, we were bound by the law, but now we are released from its condemnation and domination (7:6). The picture is that of a prisoner who has been set free. I’ve never been in prison, but I got a feel for what it must be like when I was in boot camp. We were in captivity in every sense of the word. The Coast Guard determined our schedule, our activities, what we wore, how we looked, and what we ate. Boot camp was on an island in the Oakland Bay. From our upstairs barracks window, I could see cars stuck in rush hour traffic out on the Oakland freeway. I thought, “Those drivers are probably grumbling about the traffic, but if they only knew how free they are to be able to drive their own car wherever they want to go, they’d quit complaining!” Before Christ, we were bound by the law, but now we’re free.

D. Our union with Christ is a fruitful relationship.

The reason we are joined to Christ is so “that we might bear fruit for God” (7:4). When you compare that to 7:6, “so that we serve in newness of the Spirit,” it probably refers to the fruit of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22-23), or “the fruit of the Light,” which is “all goodness and righteousness and truth, trying to learn what is pleasing to the Lord” (Eph. 5:9-10). If you’re not bearing fruit for God, you are not fulfilling the purpose for which He saved you.

E. Our union with Christ is a powerful relationship.

The law was impotent to help us obey, but Christ gives us the Holy Spirit to indwell us and empower us to overcome sin. To be under the law is to be “in the flesh” (7:5), which has no motivation or power to overcome sin. But the Spirit enables us to put to death the deeds of the body, so that we will live (8:13; Gal. 5:16-23).

F. Our union with Christ is a holy relationship.

I mentioned at the outset that being free from the law does not mean that we are free to disobey the moral commands of Scripture. But I mention it again as we close, because it is so often misunderstood or ignored. The word “serve” (7:6) is the same Greek word translated “enslaved to God” (6:22). So Christ frees us from the law to which we were bound, but not to do as we please. We’re freed from the law so that we can be enslaved to God in the newness of the Spirit. Being a slave of righteousness is true freedom!

Conclusion

Martyn Lloyd-Jones (p. 84) says, “You are either a Christian or not a Christian; you cannot be partly Christian. You are either ‘dead’ or ‘alive’; you are either ‘born’ or ‘not born’. Becoming a Christian is not a gradual process; there is nothing indeterminate about it; we either are, or we are not Christian.”

If you’re not a Christian, you are under the condemnation of the law. But if you put your trust in Christ, who bore the curse of the law, you are released from the law and joined to a loving husband so that you can bear fruit for God. That’s even better than the best of earthly marriages can be!

Why God Gave the Law (Romans 7:7-11)

Almost a quarter century ago, philosopher Allan Bloom published his best-selling The Closing of the American Mind [Simon & Schuster, 1987]. He began (p. 25):

There is one thing a professor can be absolutely certain of: almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative. If this belief is put to the test, one can count on the students’ reaction: they will be uncomprehending. That anyone should regard the proposition as not self-evident astonishes them, as though he were calling into question 2 + 2 = 4. These are things you don’t think about.

The chief virtue that this relativism seeks to inculcate is tolerance or openness. The main enemy of tolerance is the person who thinks that he has the truth or is right in his views. This only “led to wars, persecutions, slavery, xenophobia, racism, and chauvinism. The point,” says Bloom (p. 26), “is not to correct the mistakes and really be right; rather it is not to think you are right at all.”

Bloom later (p. 67) reports his students’ reaction to his question, “Who do you think is evil?” They immediately respond, “Hitler.” They rarely mention Stalin. A few in the early 80’s mentioned Nixon, but by the time Bloom wrote the book, Nixon was being rehabilitated. Bloom comments (ibid.),

And there it stops. They have no idea of evil; they doubt its existence. Hitler is just another abstraction, an item to fill up an empty category. Although they live in a world in which the most terrible deeds are being performed and they see brutal crime in the streets, they turn aside. Perhaps they believe that evil deeds are performed by persons who, if they got the proper therapy, would not do them again—that there are evil deeds, not evil people.

I cite Bloom because the worldview of the young people that he observed a quarter century ago is now pervasive in our society. And the worldly relativism that minimizes or even eliminates the concept of sin is not just “out there.” It has flooded into the church. Popular megachurches thrive by making the church “a safe place” for everyone, where no one will be judged and where various types of immorality are relabeled as personal preferences. The “gospel” gets retooled as a way that Jesus can help you succeed and reach your personal goals. If you want your church to grow, you should never mention anything negative, like sin. Rather, tell people how much God loves them because they are so lovable. Build their self-esteem, but never suggest that they are sinners!

But if we are not sinners, then we do not need a Savior who died to bear the penalty of our sin. More than a century ago, Charles Spurgeon lamented (C. H. Spurgeon Autobiography, The Early Years [Banner of Truth], p. 54), “Too many think lightly of sin, and therefore think lightly of the Saviour.” Martyn Lloyd-Jones observed (Romans: The Law: Its Functions and Limits [Zondervan], p. 151), “The biblical doctrine of sin is absolutely crucial to an understanding of the biblical doctrine of salvation. Whatever we may think, we cannot be right and clear about the way of salvation unless we are right and clear about sin.” And since Romans 7 is one of the most penetrating analyses of sin in all of Scripture, we need to understand Paul’s thought here.

In our text, Paul defends the integrity and righteousness of God’s law against critics who argued that Paul’s teaching implied that the law is sin. “May it never be,” he exclaims (7:7). He exonerates God’s law as holy, righteous, and good (7:12), while showing why God gave the law:

God gave His law to convict us of our sin and bring us to the end of ourselves so that we would flee to Christ for salvation.

Our innate self-righteousness is so entrenched that until the law strips us of it and convicts us of our sin, we will not cast ourselves totally upon Christ. Our culture adds to this by telling us that we’re not sinners. We’re not worms, for goodness sake! We’re pretty good folks. We may want to bring Jesus into our lives as a useful coach or helper in our self-improvement program. But to trust Him as our Savior, we have to see the depth of our sin as God’s law exposes it for what it is. That’s what Paul describes here.

We come here to one of the most difficult and controversial sections of Romans. In verses 7-25, Paul dramatically shifts to the first person singular, dropping it again in chapter 8. In 7:7-13, he uses the past tense, but then in 7:14-25 he shifts to the present tense. Scholars debate whether Paul is speaking autobiographically or not. At the crux of this debate is when Paul possibly could have been “alive apart from the law” (7:9). There is also much controversy over whether verses 14-25 describe Paul before he was saved, Paul as a new believer, or Paul as a mature believer. So it’s a very difficult passage, with competent, godly scholars in every camp. I do not claim infallibility as we proceed (not that I ever do)!

Paul’s main concern in this chapter is not to share his personal experience, but rather to exonerate God’s law from any hint of being evil. He uses his own experience (as I understand it) to show how the law functions to bring conviction of sin, but also how it is powerless to deliver us from sin’s grip. Rather, it drives us to Christ, who alone has the power to save (7:25); and to the indwelling Holy Spirit, who gives us the power to overcome sin (8:2-4). So, let’s try to work through these verses.

1. The law is not sin, but it does reveal our sin (7:7).

Romans 7:7: “What shall we say then? Is the Law sin? May it never be! On the contrary, I would not have come to know sin except through the Law; for I would not have known about coveting if the Law had not said, ‘You shall not covet.’”

Paul is responding to the charge that critics would bring in reaction to 7:5: “For while we were in the flesh, the sinful passions, which were aroused by the Law, were at work in the members of our body to bear fruit for death.” The Jews believed that God gave the law to give us life and make us holy, but Paul claimed that the Law aroused us to sin, resulting in death. So now he answers this charge: “Is the Law sin?”

After strongly rejecting that slur against his teaching, Paul argues that the law functions to reveal our sin to us. He uses as a personal example the tenth commandment against coveting. This shows that by “the law” Paul mainly had in mind the Ten Commandments as the embodiment of God’s requirements for holy living. Probably he picked the tenth commandment because it is the only command that explicitly condemns evil on the heart level. Jesus pointed out that the commands against murder and adultery (and, by implication, all of the commands) go deeper than the outward action. If you’re angry at your brother, you have violated the command against murder. If you lust in your heart over a woman, you have committed adultery in God’s sight (Matt. 5:21-30). But the command against coveting explicitly goes right to the heart. Coveting concerns your heart’s desires, whether you ever act on those desires or not.

When Paul says, “I would not have come to know sin except through the Law,” he does not mean that he (or others) do not know sin at all apart from the law. He has already said (2:14-15) that Gentiles who do not have the law have the “work of the Law written in their hearts.” People sinned from Adam until Moses, even though they did not have the written law (5:12-14).

What Paul means is that the law, especially the tenth commandment focusing on the inward desires, nailed him so that he came to know sin as sin against God. Before his conversion, outwardly Paul was a self-righteous Pharisee. He thought that all of his deeds commended him to God. With regard to the law, he saw himself as “blameless” (Phil. 3:6). But when the Holy Spirit brought the tenth commandment about coveting home to his conscience, Paul realized that he had violated God’s holy law. At that point, he came to know sin. The commandment made it explicit: “Paul, you are a sinner!”

Like Paul before his conversion, most people think that they are basically good. Sure, they know they have their faults. Who doesn’t? They’re not perfect, but they are good. They excuse even their bad sins, just as Paul excused his violent persecution of the church. After all, it was justified because it was for a good cause.

So guys excuse a little pornography because, “After all, everyone looks at that stuff and I’m not hurting anyone. Besides, I’ve never cheated on my wife.” And they excuse their violent temper because that person had it coming and, “Hey, I didn’t hurt him; I just told him off!” People excuse all manner of sin and still think of themselves as basically good people because they have not come to know God’s law, especially the law as it confronts our evil desires. At the heart of coveting is the enthronement of self as lord.

Spurgeon (“The Soul’s Great Crisis,” Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit [Pilgrim Publications], 61:425) compares the sinner who thinks that he is basically good, but won’t look at God’s law, to a man who thinks he is rich and lives in a lavish manner, but refuses to look at his books. The guy lives in style. When he gets into a financial bind, he takes out a loan, and when that one comes due, he’ll meet it with another loan. He says he is all right and he convinces himself that he is all right. At the moment he’s living as if he’s all right. But does he ever get out his accounts and take stock of his real condition? No, that’s boring. We all know where that will end—the man will go bankrupt.

In the same way, Spurgeon says, we may convince ourselves that we are right with God by brushing over our faults as no big deal. We live as if we’re good people; all is well. But if we don’t examine our true condition in light of God’s law, we’re heading for eternal bankruptcy. The law reveals our sin. But Paul goes further:

2. The law provokes sinners to sin (7:8).

Romans 7:8: “But sin, taking opportunity through the commandment, produced in me coveting of every kind; for apart from the Law, sin is dead.”

Paul personifies sin as an active force that uses the law to provoke us to commit acts of sin. By sin, Paul means sin as a principle and power, not just acts of sin (Lloyd-Jones, p. 120). He repeats the phrase again (7:11), “sin, taking opportunity through the commandment.” Opportunity was a word used for a military base of operations from which the army launched its campaigns. So sin takes God’s holy commandments and uses them to tempt us to violate those commands. It stirs up the rebel in us and makes us want to assert our right to do as we please.

James Boice (Romans: The Reign of Grace [Baker], pp. 742-743) tells a story from when he was in sixth grade. The school principal came into his classroom just before lunch and said that he had heard that some students had been bringing firecrackers to school. He went on to warn about the dangers of firecrackers and to say that anyone caught with firecrackers at school would be expelled. Well, Boice didn’t own any firecrackers and he hadn’t even thought about firecrackers. But when you get to thinking about firecrackers, it’s an intriguing subject. He then remembered that one of his friends had some.

So during his lunch break, he and a friend went by this other friend’s house, got a firecracker and returned to school. They went into a cloakroom and planned to light it and pinch it out before it exploded. But the lit fuse burned the fingers of the boy holding it. He dropped it and it exploded with a horrific bang, echoing in that old building with its high ceilings, marble floors, and plaster walls. Before the boys could stagger out of the cloakroom, the principal was out of his office, down the hall, and standing there to greet them. As Boice later sat in the principal’s office with his parents, he remembers the principal saying over and over, “I had just told them not to bring any firecrackers to school. I just can’t believe it.”

But that’s how sin operates in the hearts of rebels. It takes God’s good and right commandments and entices us to violate them. Sometimes when you read about others sinning or you see it on TV or in a movie, you think, “I’ll bet that would be fun!” You know that God forbids it, but probably He just wants to deprive you of some fun. Besides, what will it hurt to try it once? It can’t be all that bad. And, I can always get forgiven later. So our sin nature springboards off the commandment to provoke us to sin.

What does Paul mean when he says, “For apart from the Law sin is dead”? Since the fall, everyone is born in sin and is prone to sin. Before the flood, before God gave the law to Moses, the world was so sinful that we read (Gen. 6:5), “Then the Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great on the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.” So how can Paul say, “apart from the Law sin is dead”?

He must have meant, “Sin was comparatively dead; as far as his awareness was concerned it was dead” (Lloyd-Jones, p. 135). In other words, before God brought the law to bear on Paul’s conscience, as far as he knew, he wasn’t in sin. He saw himself as a good person. The law had not yet revived the sin that lay dormant in his heart. Apart from the law, sin seems to be dead as far as the sinner is concerned. Paul traces the process further:

3. The law, through our failures to keep it, brings us to the end of ourselves (7:9-11).

Romans 7:9-11: “I was once alive apart from the Law; but when the commandment came, sin became alive and I died; and this commandment, which was to result in life, proved to result in death for me; for sin, taking an opportunity through the commandment, deceived me and through it killed me.” (I will have to deal with the deceptive aspect of sin in our next study.)

What does Paul mean when he says that he was “once alive apart from the Law”? This is the same apostle who said that before salvation we all were dead in our sins (Eph. 2:1). How could he once be alive? And when was Paul ever “apart from the Law”? He was raised from his youth up in the strictest traditions of Judaism (Acts 22:3; 26:4-5; Phil. 3:5). And, when did sin “kill” him?

As with every verse in this text, there are many opinions. Some say that verse 9 refers to Adam, since he is the only one of whom it rightly could be said that he was once alive apart from the law. Others take it to refer to Israel before the law was given. But most likely, Paul is speaking in a relative sense about his own perception of himself. Once, he thought that he was alive and doing quite well in God’s sight. He saw himself as blameless with regard to the righteousness of the law (Phil. 3:6). Like the Pharisee in Jesus’ story, he would have prayed (Luke 18:11-12), “God, I thank You that I am not like other people: swindlers, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I pay tithes of all that I get.” In that sense, Paul saw himself as once alive apart from the law. He was “apart from the law” in the sense that it had not yet bore down on his conscience to convict him on the heart level.

But then “the commandment came”—“You shall not covet.” He had memorized that commandment as a child. He had recited it many times. But the Holy Spirit had not nailed him with it. Lloyd-Jones (p. 134) illustrates this with the experience that we’ve all had, where we’ve read a verse many, many times, but we’ve skipped right over it and kept going. It didn’t say anything to us. But then suddenly, it hits you. You see it as you’ve never seen it before. The commandment came to you.

Then what happens? “Sin became alive and I died” (7:9). At first, Paul thought that he was alive and sin was dead. But then, God’s law hit him and he suddenly realized that his sin was very much alive and he was dead. He saw that he was not right with God, as he formerly had thought. Rather, he was alienated from God and under His judgment. He had thought that he would get into heaven because he was a zealous Jew, and even a notch above other Jews, because he was a Pharisee. But now he realized that he was a blasphemer, a persecutor of God’s church, a violent aggressor, and the chief of sinners (1 Tim. 1:13, 15).

The commandment promised life (7:10) to all who keep it (Lev. 18:5; Ezek. 20:11). Paul thought that he had been keeping it blamelessly. But God shot the arrow of the commandment, “You shall not covet.” It hit Paul in the heart and killed him. Spurgeon (61:427) says, “What died in Paul was that which ought never to have lived. It was that great ‘I’ in Paul … that ‘I’ that used to say, ‘I thank thee that I am not like other men’—that ‘I’ that folded its arms in satisfied security—that ‘I’ that bent its knee in prayer, but never bowed down the heart in penitence—that ‘I’ died.”

Spurgeon goes on (pp. 427-428) to show several other respects in which Paul died. He died in that he saw he was condemned to die. He stood guilty before God. He died in that all his hopes from his past life died. His good works that he had been relying on came crashing down as worthless. He died in that all his hopes as to the future died. He realized that if his salvation depended on his future keeping the law, he was doomed. His past showed that he would be sure to break it again in the future. And, he died in that all his powers seemed to die. Formerly, he thought that he could keep the law just fine by his own strength. But now he saw that every thought, word, and desire that did not meet God’s holy standard would condemn him. And so all his hope died. He felt condemned. The rope was around his neck, as Spurgeon says elsewhere (Autobiography, 1:54).

Conclusion

Can you identify with Paul’s experience? Has God’s holy law hit home to your conscience so that you died to all self-righteousness? Has the law killed all your hopes that your good works will get you into heaven? If so, that’s a good thing, because Jesus didn’t come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance (Luke 5:32). When you see God’s holy standard and how miserably you have violated it over and over, you then see your need for a Savior. And the best news ever is that Jesus Christ came into this world to save sinners (1 Tim. 1:15)!

James Boice (p. 746) tells of a time when John Gerstner, who was then retired from teaching church history at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, was at a church preaching from Romans. He expounded on the law and used it to expose sin. After the service, a woman came up to him. She held up her hand with her index finger and thumb about a half-inch apart and she said, “Dr. Gerstner, you make me feel this big.”

Dr. Gerstner replied, “But madam, that’s too big. That’s much too big. Don’t you know that that much self-righteousness will take you to hell?”

God gave His law to strip us of all self-righteousness and to convict us of our sin so that we would flee to Christ to save us. Make sure that your hope for eternal life is in Christ alone!

The Utter Sinfulness of Sin (Romans 7:11-13)

In 1973, psychiatrist Karl Menninger, founder of the famous Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, wrote a best-seller titled, Whatever Became of Sin? [Bantam Books]. I didn’t read that book, but the title, especially coming from a psychiatrist, who to my knowledge was not a Christian, is significant. Menninger realized almost 40 years ago that the concept of sin was vanishing from our culture. He argued (as summarized by James Boice, Romans: The Reign of Grace [Baker], 2:747),

In the lifetimes of many of us, sin has been redefined: first, as crime—that is, as transgression of the law of man rather than transgression of the law of God—and second, as symptoms. Since “symptoms” are caused by things external to the individual, they are seen as effects for which the offender is not responsible. Thus it happened that sin against God has been redefined (and dismissed) as the unfortunate effects of bad circumstances. And no one is to blame.

We now view many behaviors that the Bible calls “sin” as psychological or emotional issues for which therapy, not repentance, is the solution. I’ve read polls that show that even among evangelical Christians, many do not view premarital sex or homosexual behavior as sin. Churches offer anger management classes (not anger repentance classes) or groups to help you overcome your “addictions” (not sins). Sin has become a disease that we treat therapeutically, not a behavior for which we’re responsible.

Christians regularly watch Hollywood’s latest movies that are rife with filthy language, sexual scenes, and violence, without any concern that they are disobeying Scripture, which commands (Eph. 5:3-4), “But immorality or any impurity or greed must not even be named among you, as is proper among saints; and there must be no filthiness and silly talk, or coarse jesting, which are not fitting, but rather giving of thanks.” So Dr. Menninger was quite right to ask, “Whatever became of sin?”

In our text, Paul is defending himself against critics who alleged that he taught that the law is sin. Paul has been teaching that if you try to gain right standing with God by keeping the law, you are doomed to fail. The law was not given to make us right before God. To the contrary, “through the Law comes the knowledge of sin” (Rom. 3:20). “The Law brings about wrath” (4:15). “The Law came in so that the transgression would increase” (5:20). And so Paul shows (7:4) that through our union with Christ, we died to the law in order that we might bear fruit for God. We have been released from the law so that now “we serve in newness of the Spirit and not in oldness of the letter” (7:6).

Paul knew that critics would react to this teaching by accusing him of saying that the law is sin. His response is (7:7), “May it never be!” The problem is not with the law. Rather, the problem is our sin. When you mix God’s holy law with our sin, it produces negative results, much like mixing two incompatible chemicals.

Verses 11 & 12 wrap up Paul’s argument that the law is not the problem; rather, sin is the problem. As we saw last time, he personifies sin as an active force. Verse 13 serves as a hinge verse, restating the argument from 7:7-12 while also introducing 7:14-25. We can sum up his thought in 7:11-13:

God’s law reveals the holiness of His commandments and the utter sinfulness of sin so that we will hate our sin.

1. God’s law reveals the holiness of His commandments.

Paul concludes (7:12), “So then, the Law is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good.”

By “the Law,” Paul means the law as a whole. When he repeats, “the commandment,” he may be referring to the tenth commandment against coveting that he has just mentioned (7:7), or to the moral commands. But he means that the law as a whole and every single part of it is “holy and righteous and good.” He piles up these terms to emphasize his point (in 7:7) that the law is not in any way sinful. The reason that the law is holy, righteous, and good is that it was given to us by God who is holy, righteous, and good.

God’s law is holy. God’s holiness means that He is altogether separate from us and separate from sin. Christ’s aim for His church is that “she would be holy and blameless” (Eph. 5:27). Applied to us, God’s holy commandments show us how to live separately from this evil world, in a manner pleasing to the Lord.

That God’s law is righteous means that it is right or just. God Himself is the standard of what is right. Moses says of God (Deut. 32:4), “For all His ways are just; a God of faithfulness and without injustice, righteous and upright is He.” If we violate God’s moral commands, we are wrong because God is always right. His standards are not relative, changing with the culture or over time. We can’t persuade Him to bend His righteous commands to fit what we may think is right.

God’s commandments are also good because they come from God who is always good. As with righteousness, God is the final standard of what is good (Luke 18:19). This means that all of God’s commandments are for our good. To violate His commands is to bring trouble and hardship on ourselves. If we want to live the truly “good life,” then we must follow God’s good commands.

Since as new covenant believers we are not under the Law of Moses, we may wonder, “Which of the Old Testament commands apply to us? Are we obligated to keep the Ten Commandments, since Paul calls them a ‘ministry of death, in letters engraved on stones’” (2 Cor. 3:7)?

In the sense that the Ten Commandments serve as a summary of the two great commandments, to love God and love others, they are valid and binding for today. Also, all of the Ten Commandments, except for the Sabbath command, are repeated in the New Testament. The Sabbath command, as I understand it, was fulfilled in Christ (Heb. 4:1-11; Rom. 14:5; Col. 2:16). The exhortation to us is not to forsake assembling together (Heb. 10:25), but we are not under that command in the legal sense of the Old Testament. (See my message, “God’s Day of Rest,” from Gen. 2:1-3, 12/17/95, on the church website for my further thoughts on this.)

So Paul wants us to be clear that God’s law is holy, righteous, and good. Being under grace does not mean living in a lawless manner (1 John 3:4; 1 Cor. 9:21).

2. God’s law reveals the utter sinfulness of sin.

Paul concludes (7:13c), “so that through the commandment sin would become utterly sinful.” As C. H. Spurgeon put it (Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit [Pilgrim Publications], 59:469), “[The law] was not the cure of the disease, much less the creator of it, but it was the revealer of the disease that lurked in the constitution of man.” He goes on to show that when Paul wanted to come up with a word to describe how bad sin is, he didn’t call it exceedingly black or horrible or deadly. Rather, when he wanted to find the very worst word, he called sin by its own name—it is exceedingly sinful. There is nothing as evil as sin. God gave His law for our good (Deut. 10:13), and so when we deliberately throw it off and trample it under foot, that law exposes the utter sinfulness of our sin in at least four ways:

A. Sin is utterly sinful because it is rebellion against our loving and kind Heavenly Father.

When God gave Adam and Eve the command not to eat of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, that command was for their good, to keep them from the consequence of death (Gen. 2:16-17). We can compare it to parents who tell their little children not to run into a busy street. That command is not to deprive the children of fun, but to protect them from death. So when we sin, we rebel against the God who is loving and kind towards us. He is never mean, harsh, or cruel. Rather, sin (as Spurgeon put it in another sermon) is the monster that this verse drags to light (ibid., 19:73). We need to see sin for what it is, rebellion against our loving and kind Heavenly Father.

B. Sin is utterly sinful because it takes a good thing and uses it to kill us.

Sin takes the good law and turns it into an instrument of death. It would be like taking a scalpel and using it to murder someone. Is the scalpel bad? No! The scalpel is a good and useful tool in the hands of a skilled physician. The sinner who used the scalpel to murder someone is the culprit. Sin takes God’s holy commandments and uses them to kill us. (Paul mentions “death” or “killed” in 7:9, 10, 11, & 13.) He means that the law brings us under God’s righteous, eternal condemnation because we have deliberately violated it over and over. So we should fight against our sin with as much effort as we would struggle against an intruder who broke into our house and was attempting to murder us.

C. Sin is utterly sinful because it involves deliberate violation of God’s good and perfect will for us.

As Paul said (4:15), “Where there is no law, there also is no violation.” This is not to say that people did not sin before the law (5:13-14), but rather to say that the law heightens the sinfulness of sin by showing that we are deliberately going against what God has commanded for our good. Our conscience may nag at us that something is wrong. But when we read the explicit command in the Bible and then go against it, we’re just thumbing our nose at God. We’re saying, “God, You don’t know what is best for me! I know better than You do, and I’m going my own way.” The commandment shows sin to be utterly sinful.

D. Sin is utterly sinful because it uses deception to kill us.

In his book and film, “Peace Child,” missionary Don Richardson told about the wicked practice of the Sawi tribe before he brought the gospel to them. They extolled deception as a virtue. They would lure an outsider into their midst as a friend, who didn’t suspect their treachery. They would treat him as a king and feed him well, but they were literally fattening him for the slaughter. At the opportune time, when the victim thought that the Sawi tribal leaders were his friends, they would sadistically smile as they killed him, and then they would eat him. And so when Richardson first told them the story of Jesus, they thought that Judas was the real hero! He used deception to kill Jesus. In the same way, sin is utterly sinful because it uses deception to kill us.

In two other places (2 Cor. 11:3; 1 Tim. 2:14) Paul uses the same verb, “deceived” (Rom. 7:11) to describe the serpent’s deception of Eve in the garden. One commentator (C. E. B. Cranfield, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans [T. & T. Clark], 1:352-353) shows three ways that the serpent deceived Eve. First, he distorted and misrepresented God’s commandment by drawing attention only to the negative part of it and ignoring the positive. Second, he made her believe that God would not punish disobedience with death, as He had warned. Third, he used the very commandment itself to insinuate doubts about God’s good will and to suggest the possibility that she and Adam could assert themselves in opposition to God. Martyn Lloyd-Jones (Romans: The Law: Its Functions and Limits [Zondervan], pp. 155-160) lists nine ways that sin deceives us. I’ve incorporated his list into my own list of 15 ways that sin deceives us. I don’t expect you to remember all of these, but by piling them up without much comment, I want you to see how dangerous of an enemy sin really is.

(1). Sin deceives us into thinking that outward obedience alone pleases God, whereas we need to please Him on the heart level.

This was the downfall of the Pharisees. They thought that they were keeping all of God’s commandments, but Jesus rebuked them because their hearts were far from God (Mark 7:6-7; Matt. 23:25). Sin deceives us so that we congratulate ourselves for our outward obedience to God, but all the while our hearts are corrupt. “Sure, I look at some porn, but at least I’ve never cheated on my wife.” “Sure, I’m bitter over what he did to me, but I haven’t killed him.” But God looks on the thoughts and intentions of the heart (Heb. 4:12).

(2). Sometimes sin changes its tactics and tells us that everything is hopeless, so we might as well keep on sinning.

We wrongly conclude, “I’ve failed again and again, so there is no hope for me. I might as well just give in and go on sinning.”

(3). Sin deceives us to presume on God’s grace.

Sin tells us that it doesn’t matter whether or not we are holy. It says, “Don’t worry about your sin. It’s not hurting anyone. Besides, you can always get forgiven later.”

(4). Sin deceives us into thinking that it will bring true and lasting happiness, while holiness will bring us misery.

This is such a common ploy that you would think that we’d see right through it. But it works over and over again. “An affair will bring happiness, but being faithful to your marriage vows will make you miserable.” Related to this is the next form of deception:

(5). Sin deceives us into thinking that we have a right to happiness, while we forget that we have a responsibility to holiness.

I’ve known Christians who walk away from their marriages with the excuse, “I deserve some happiness in my life. My marriage has only brought me misery. How can this new relationship be wrong when it makes me so happy?” That’s the defense of a well-known Christian singer who divorced her husband and married another singer who divorced his wife. I recently read an article that tried to convince the readers that this sinful behavior was all right, because now she and her new husband are so happy. But what about the biblical command to be holy?

(6). Sin deceives us by getting us to discount the consequences of willful disobedience.

Satan lied to Eve (Gen. 3:4), “You surely will not die!” God would not be so mean as to impose such harsh consequences for such a minor thing as eating a piece of fruit, would He? God is loving and gracious; He won’t punish your sin!

(7). Sin deceives us into thinking that we’ve earned some free passes to sin because of all that we’ve done to serve God.

This may have been what led to David’s downfall. He was the king—didn’t that give him some extra privileges? He had written many psalms. He had fought and won many battles. Didn’t he deserve a “break”? Several years ago, a well known pastor was exposed when it came out that he “relieved the stress” of his ministry responsibilities by going to a homosexual prostitute! Talk about being deceived!

(8). Sin deceives us by getting us to swap the labels and call it something much more acceptable.

It is not adultery; it’s an affair or a fling. It’s not perversion; it’s being gay. It’s not stealing; it’s just taking what the company owes me but doesn’t pay me. I’m not angry; I just have a short fuse. It’s not gossip; I just wanted to share a prayer concern.

(9). Sin deceives us by making us think that we’re normal when we sin and to think that holy people are weird.

We look around at the world and conclude that yielding to temptation is normal. The weirdoes are those holy people who obey God. Or, we think, “I’ll bet that they’re no different than I am. They probably engage in some secret sins, but they’re hypocrites. At least I’m honest about who I am.”

(10). Sin deceives us by working by degrees, so that eventually that which would have shocked us is now accepted as normal.

When I used to paint houses, the home owner would walk in and make a big deal about the smell of the paint. But I was so used to it that I didn’t even notice. The prophet Hosea chided “Ephraim,” or Israel (Hos.7:9): “Gray hairs are sprinkled on him, yet he does not know it.” Can you imagine someone going gray without being aware of it? But the prophet was using this humorous analogy to show how we drift spiritually without being aware of how far off course we really are. The first time you watch a sex scene in a movie, it shocks you. But after you’ve seen such filth a few dozen times, you just shrug it off as no big deal. When you first hear profanity, it jars you. But after being around it a while, you don’t even wince and you may even toss off a bad word or two yourself without being aware of it.

(11). Sin deceives us by making us angry at the law, feeling that God is against us when He prohibits something.

Sin gets us to believe that God and His law are unreasonable, impossible, and unjust. “Does He expect me to be perfect? Why doesn’t He give me a break now and then? He must not care about me or He wouldn’t give such unreasonable commands!”

(12). Sin deceives us by making us think very highly of ourselves.

“You’re smart enough to figure out what is best for you. You’re able to determine right and wrong without putting yourself under God’s legalistic standards. Think for yourself!”

(13). Sin tells us that the law is oppressive, keeping us from developing the gifts and talents we have within us.

“God’s moral standards are holding you back from reaching your full potential! Use the brain that God gave you! You don’t have to be restricted by that outdated book, the Bible!”

(14). Sin makes righteousness look drab and unattractive.

“You’ve only had sex with your marriage partner? How boring! You go to church every Sunday? How restrictive! What a way to mess up your weekend!”

(15). Sin deceives us by getting us to compare ourselves with other sinners, rather than to compare ourselves to God’s holy standard.

The psalmist says that sin flatters us in our own eyes (Ps. 36:2). It makes us think that we’re not so bad because we compare our relatively “minor faults” with the really bad things that others do. By comparison, we’re not so bad. But the standard is not what others do or what we do, but what God’s Word commands.

Thus God’s law reveals the holiness and goodness of His commands, along with the utter sinfulness of sin. What should our response be?

3. The practical result of understanding the holiness of God’s commands and the utter sinfulness of sin is that we should hate our own sin.

I am inferring this, since Paul doesn’t state it directly here, although he does go on (7:14-25) to show how much he hates his own propensity towards sin. But the Bible is clear: “Hate evil, you who love the Lord” (Ps. 97:10a). And we’re not just supposed to hate the evil in others, but first and foremost, we need to hate our own sin. Take the log out of your own eye first (Matt. 7:5). It was Paul’s hatred of his own sin that caused him to cry out (Rom. 7:24), “Wretched man that I am! Who will set me free from the body of this death?”

Conclusion

Do you hate your own sin? Do you hate it enough to stop making excuses for it and to give serious thought and effort as to how not to sin? Sin is ugly, ugly, ugly! To watch a believer fall into sin is like watching a dog licking up its own vomit (2 Pet. 2:22). God’s Word shows us how walk in the light so that we do not fall into the mire of sin. Love the Word! Read it! Memorize it! Obey it! Don’t let sin kill you. Rather, hate your sin enough to kill it!

Who is This Wretched Man? (Romans 7:14-25, Overview)

We come now to one of the most difficult passages to interpret in the Book of Romans. With the exception of certain prophetic texts, there are not many other passages in Scripture where there is such widespread difference of opinion among godly scholars as there is for Romans 7:14-25. Is Paul describing his own experience here? If so, is it his experience before he was saved, his experience as an immature believer, or his experience as a mature believer? Since Paul is in the midst of teaching us how to overcome sin in our daily experience, it’s an important text to understand. But we can’t apply it correctly until we first understand it correctly.

In this message, I want to give an overview of the various views and their main arguments. In subsequent messages I’ll work through the text in more detail. When you come to a text where so many godly men differ, it’s important to be gracious towards those who differ and acknowledge that there is no neat, tidy view that answers all the difficulties. Each view has its strengths and weaknesses, and so you have to pick which weaknesses you’re willing to live with in the view that you adopt. If someone claims to have solved all the problems, he is blind to the weaknesses of his view. If we could solve all the difficulties, then everyone would agree.

Also, when you come to a difficult text, it’s important to interpret it in light of other texts that are more clear. We need to try to harmonize and integrate this text into the flow of Paul’s unambiguous teaching elsewhere. And, as always, we need to confess our lack of understanding to the Lord and ask Him to give us insight through the Holy Spirit so that we will grow in godliness. Our aim is not just to solve the interpretive puzzle, but to become more like Jesus Christ.

The main problem that we have to grapple with here is that some statements make it sound as if Paul were not a believer, whereas other statements make it sound as if he were a believer. Among those who argue that Paul is describing the experience of an unbeliever, some say that it is the experience of a Jew under the law. Some say that it describes a man under deep conviction of sin just before his conversion. Among those who argue that it describes a believer, some argue that he is talking about the normal experience of a mature Christian, whereas others say that he is describing the experience of a new or very immature believer.

Some argue that Paul is not speaking autobiographically here, but it seems to me that he is describing himself here. He uses “I” 24 times in 7:14-25, plus “me,” “my,” or “myself” 14 times. While Paul could be using this as a literary device, the most obvious way to take it is that he is speaking of his own experience. Obviously his experience is representative of the experience of all who have struggled against sin. But we’re learning through Paul’s experience.

Also, we need to keep in mind that Paul’s main purpose is not to share this as an interesting story, but rather to establish the holiness and integrity of the law, while at the same time to show the law’s inability to deliver us from sin. To have consistent victory over sin, we must learn to rely moment by moment on the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit, which Paul explains in chapter 8.

With that as a background, let me walk you through some of the arguments for the various views. There are a number of variants within each view which we will not have time to delve into.

Romans 7:14-25 describes an unbeliever.

This was the position of the early church fathers in the first three centuries of Christianity. Augustine held this view earlier in his Christian life, but later argued that it refers to believers. John Wesley and many in the Arminian camp hold to this view. Here are the strongest arguments for this view:

1. Paul uses language throughout the passage that could only be descriptive of an unbeliever.

This is the strongest argument for this position. In 7:14, Paul laments, “I am of flesh, sold into bondage to sin.” But in 6:14, he stated as a matter of fact, “For sin shall not be master over you.” He also stated (6:17-18), “But thanks be to God that though you were slaves of sin, you became obedient from the heart to that form of teaching to which you were committed, and having been freed from sin, you became slaves of righteousness.” He reinforces this in 6:22, “But now having been freed from sin and enslaved to God, you derive your benefit, resulting in sanctification, and the outcome, eternal life.”

Also, in 6:2, Paul said, “How shall we who died to sin still live in it?” But in 7:25b he says that with his flesh he is serving (the word means, “to serve as a slave”) the law of sin. In 6:6, he says that we were crucified with Christ so that our body of sin might be done away with, so that we would no longer be slaves to sin. But in 7:24 he laments, “Who will set me free from the body of this death?” In 7:18 Paul says, “For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh.” How could a man indwelled by the Holy Spirit say such a thing? In 7:23 he adds that he is “a prisoner of the law of sin.” And, how could a believer who has already been redeemed by Christ cry out (7:24), “Wretched man that I am! Who will set me free from the body of this death?”

So the descriptions of our new position in Christ as believers in chapter 6 are totally at odds with these statements of the wretched man in chapter 7. He must still be an unbeliever.

2. The flow of the context argues for 7:14-25 being a description of unbelievers.

Almost everyone agrees that 7:7-13 describes Paul as an unbeliever. If 7:14 shifts to his experience as a believer, you would expect a disjunctive word, such as “but.” Instead, Paul uses “for,” which indicates that he is explaining further his experience as an unbeliever. This is further substantiated by his immediately stating that he is “of flesh, sold into bondage to sin.” This goes back to 7:5, where Paul describes his experience as an unbeliever as being “in the flesh.”

Also, some argue that our text describes further the experience of 7:5, of the unbeliever in the flesh, whereas 8:1-17 picks up on 7:6, which describes the newness of serving in the Spirit. Also, there is the dramatic shift between the miserable experience of 7:14-25 and the “now” of 8:1 and the experience of victory that follows. Douglas Moo (The Epistle to the Romans [Eerdmans], pp. 442-451) argues that Paul presents his experience as a representative Jewish unbeliever under the law to show that the law is impotent to save anyone from their sin, thus reinforcing the argument of 7:1-13. He also is persuaded by the contrasts mentioned under the first argument.

3. In 7:14-25, there is an absence of any references to the Holy Spirit, who indwells all believers, whereas in chapter 8, the Holy Spirit is mentioned frequently.

Paul makes it clear (in 8:9) that every believer is indwelled with the Holy Spirit. If you do not have the Holy Spirit, you do not belong to Christ. Since there is a glaring absence of any mention of the Spirit in 7:14-25, as contrasted with at least 17 references to the Spirit in chapter 8, chapter 7 must describe an unbeliever.

4. The person in 7:14-25 is not just struggling with sin but is defeated by sin.

Elsewhere Paul makes it clear that all believers struggle with sin, but that’s not what he describes in these verses. His experience in 7:14-25 is not just a struggle, but one of repeated failure, defeat, and inability to obey God. This is descriptive of an unbeliever.

There are some variations of the view that these verses describe an unbeliever. Martyn Lloyd-Jones argues for the position (also held by Godet and the Pietists, Francke and Bengel), that Paul is describing the experience of a Jew who is under deep conviction of sin, but not yet reborn. Thomas Schreiner (Romans [Baker], p. 390) argues that “Paul does not intend to distinguish believers from unbelievers in this text.” Rather, “Paul reflects on whether the law has the ability to transform human beings, concluding that it does not.” So Schreiner says that the passage could be describing either unbelievers or believers. Stuart Briscoe (The Communicator’s Commentary [Word], p. 147), somewhat in line with Schreiner, holds that “Paul is relating the struggles he had with the law of God before he knew Christ and which he continues to have since coming into an experience of the risen Lord.”

Romans 7:14-25 describes a mature believer.

This was the view of Augustine later in life, as already mentioned. It is also the view of Luther, Calvin, and most of the Reformers, along with Reformed men down through the centuries, such as John Owen, Charles Hodge, John Murray, James Boice, J. I. Packer, John Piper, and others. Here are the main arguments to support the view that Paul is describing the experience of a mature believer. (John Piper gives ten arguments in favor of this view, but I can only list a few.)

1. The shift to the present tense argues that Paul is speaking of his present experience as a mature believer.

As I’ve noted, Paul makes a very obvious shift from past tense verbs in 7:7-13 to present tense verbs in 7:14-25. The most natural way to understand this is that Paul is here describing his ongoing struggle against sin when he wrote this letter.

2. The context of Romans 6-8 is a discussion of sanctification in the Christian life, not of an unbeliever’s struggle with the law.

3. If 7:14-25 describes Paul’s pre-conversion experience, it is in conflict with how he describes that experience elsewhere.

In Philippians 3 and in Galatians 1, along with a couple of places in Acts, Paul portrays himself before conversion as a self-satisfied Jew, bent on persecuting the church. There is no record that he went through an intense inward conflict such as that described here.

4. Paul’s desires in these verses are those of a believer, not of an unbeliever.

He says (7:22), “For I joyfully concur with the law of God in the inner man.” He is seeking to obey the law, not just outwardly, but with the “inner man” (7:15-20, 22). Unbelievers may put on an outward show of obedience, but their hearts are far from God (Matt. 23; Mark 7:6-13). Unbelievers do not seek after God (Rom. 3:11) or desire to please Him (8:8). His heartfelt cry, “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” sounds like the cry of a man who yearns for God and the new resurrection body, which will be free from sin. The closer a man draws to God, the more he sees the corruption of his old nature and the more he desires to be free from all inclination to sin.

5. The battle between the two “I’s” describes a believer, not an unbeliever.

Unbelievers only live in the flesh, but believers have a new nature and the indwelling Holy Spirit that war against the flesh (Gal. 5:17). Every Christian who is honest acknowledges this inner struggle against sin that goes on throughout life. Paul’s lament (7:18), “For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh,” indicates that there is more to Paul than just flesh. He has a new inner man that longs for God and His holiness, although he has not yet attained it.

There are more arguments for each side and each side has arguments to rebut the arguments of the other side. For sake of time, I cannot go through each of these. Rather, I will now give you the correct view (yeah, sure!). As I said, there are strengths and weaknesses with every view, so we have to pick a view that seems most to harmonize with other Scriptures and to have the fewest problems. I actually was pushed toward this view by reading Martyn Lloyd-Jones’ volume on Romans 7 where he argues that these verses describe a Jew under intense conviction of sin, just prior to conversion. (He would not be happy that his argument pushed me in this direction!)

Romans 7:14-25 describes an immature believer who has not yet learned that he is free from the law and that he has the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit to overcome sin.

Let me begin by acknowledging that the main weakness of this view is Paul’s use of the present tense. It sounds as if Paul is speaking of his current experience, not of a past experience that he had as a new believer. But Paul could be using the present tense as a vivid way of sharing his experiences as a new believer. For reasons that I will share in a moment, I cannot accept that Paul is describing his experience as a mature believer.

Also, I want to distance myself from what is called the Keswick teaching, popularized by Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret, Watchman Nee’s The Normal Christian Life and Ian Thomas’ The Saving Life of Christ. These and other books of this persuasion teach that Romans 7 describes a “carnal” Christian who has not yet learned the secret of the “exchanged life.” When you learn the secret, “not I, but Christ,” you break through into the experience of Romans 8. It is sometimes pictured as moving from the wilderness to the Promised Land. This teaching gives the impression that once you break into the Romans 8 experience, the Christian life becomes an effortless, struggle-free, sin-free life. You never worry, you’re never ruffled by trials, and you experience perpetual joy and close fellowship with the Lord. These books convey that if you’re struggling against sin, you haven’t learned the secret of letting go and letting God. That is not my understanding of the biblical Christian life!

I understand the Christian life to be an ongoing, lifelong struggle against the world, the flesh, and the devil. We never arrive at a place in this life where sin no longer tempts us, where trials are not a difficult burden, and where we have attained sinless perfection. Jesus Himself cried out to God with loud crying and tears (Heb. 5:7). Paul was burdened so much that he despaired of life itself (2 Cor. 1:8). He describes his Christian life as a fight, not an effortless rest (2 Tim. 4:7). The author of Hebrews commends his readers in their striving against sin, and encourages them to submit to the difficult discipline of the Lord that for the moment does not seem joyful, but sorrowful (Heb. 12:4-11). So I’m not saying that in moving from Romans 7 to Romans 8, life becomes an effortless, ecstatic experience of perpetual victory. Even mature believers fall into sin on occasions and they always fall far short of perfection.

This means that there is always going to be some degree of the struggle expressed in Romans 7 in the Christian life, even in Romans 8. In that, I agree with those who argue that this is the experience of a mature Christian. As we grow to know God and His ways more deeply, we will always be painfully aware of how far short we fall. We will always lament our propensity toward living in the flesh and yielding to the sin that so easily besets us. There will always be the battle between the two natures. I do not agree with those who say that believers only have the new nature, or that we only sin occasionally. It is a daily battle with many setbacks.

But I disagree with those who argue that Romans 7 describes the “normal” Christian life. The man in Romans 7 is not just struggling against sin, which every Christian must do all through life, but he is consistently defeated by sin. He describes himself as “sold into bondage to sin” (7:14). He is “not practicing” what he would like to do, but is doing the very thing he hates (7:15). He wills to do good, but he does not do it (7:18). He practices the very evil that he does not want to do (7:19). He describes himself as a prisoner of the law of sin (7:23). These descriptions are contrary to 1 John 3:9, which says that believers cannot continue to sin as a normal way of life. Believers do sin, but they do not live in perpetual defeat to sin as Paul here describes. Mature believers do not continue practicing sin or living in slavery to it.

I’m sensitive to the argument that in light of chapter 6, no believer could say that he is “sold into bondage to sin” and “a prisoner of the law of sin.” As I said, that is the strongest argument that this is an unbeliever. But an unbeliever would not experience this intense hatred of his sin and inner desire to be free from it. And a mature believer would not describe himself as being in bondage to sin. Thus I think that Paul is describing his experience as a new believer, before he understood that he had died to the law and been joined in marriage to Christ and before he learned to walk by means of the Holy Spirit.

Since Paul before his conversion was a legalistic Pharisee, it’s not likely that immediately after his conversion he understood that he was dead to the law or that he now could live by the power of the Holy Spirit. He probably began his Christian experience by striving to obey the law in the flesh. After a time of trying and failing and trying again and failing again, he finally broke through to realize, “Sin shall not be master over you, for you are not under law, but under grace” (6:14). He came to understand that since he was identified with Christ in His death, he was now free from the law, so that now he could serve in newness of the Spirit (7:4, 6). He grew to understand his new identity in Christ. He realized the glorious truth, “Therefore there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (8:1). But it probably took him a while, perhaps a few years, to work through all of this both theologically and practically in terms of his daily experience. My understanding is that he is sharing those early struggles in Romans 7:14-25.

Conclusion

I’ll go back and work through these verses in more detail in coming messages. But for now, let me leave you with a few practical issues to think about.

First, if you do not hate your sin and struggle against it, you need to examine whether you are saved. Those who have experienced the new birth hate their sin and they desperately want to have victory over it. If you shrug off your sin as no big deal, it is not a sign that the Holy Spirit is dwelling in you. A life of ongoing repentance is the mark of the new birth.

Second, if you have trusted Christ but are defeated often by sin, so that you feel in bondage to it, there is hope for deliverance. Your defeats do not necessarily mean that you are not born again. At the same time, you need to realize how serious your sins are and that God did not save you so that you would live a defeated life. He has provided the Word, the indwelling Holy Spirit, and the body of Christ to help every Christian gain consistent victory over sin, beginning on the thought level. We will never be sinless in this life, but we should be sinning less as we grow to maturity in Christ. If you learn to walk in the Spirit, you will not carry out the desire of the flesh (Gal. 5:16).

So wherever you’re at spiritually, I want to offer you genuine hope in the Lord. If you are not saved, cry out to God: “Whoever will call on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Rom. 10:13). If you are defeated by sin, so was none other than the apostle Paul. But he learned to live in consistent victory in Christ, and so can you! Romans 8 will help point the way.

The Merry-Go-Round of Sin (Romans 7:14-20)

Have you ever felt like you were on a merry-go-round of sin, but you couldn’t figure out how to get off even though you wanted to? In that sense, it isn’t a merry-go-round, but a miserable-go-round! You hate going around and around, but you don’t know how to get off the stupid thing.

That’s what Paul describes in Romans 7:14-20 about his spiritual experience: he hates what he is doing, but he can’t stop doing it. He knows that God gave us the law; it’s spiritual and good; it’s the right thing to do. The problem is, he can’t do it. He doesn’t have the power to get off the merry-go-round of sin.

But the problem we face in trying to understand Paul (as I explained at length last week) is that it’s difficult to determine whether he is talking here about his experience before salvation or after he was saved. Some of his statements sound as if he was an unbeliever, but other statements sound as if he was a believer. And, if it refers to his experience as a believer, how then do his words about being in bondage to sin (7:14) square with what he has said in chapter 6 about being freed from sin?

My understanding is that Paul is describing his experience as an immature believer, before he came to understand that he was no longer under the law and that he could experience consistent victory over sin by relying on the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit. I hold this view because Paul makes some statements that an unbeliever could not make. He loves God’s law and wants to keep it from the heart (7:22). He hates his own sin.

But he also makes some statements that a mature believer could not make. He is not merely describing the ongoing struggle against sin that all believers experience, but rather an experience of ongoing defeat. He was habitually practicing the very evil that he hated (7:15, 19). This does not square with a person who walks by means of the Spirit and thus does not fulfill the desires of the flesh (Gal. 5:16). It does not line up with 1 John 3:9 (and 2:3-6), that those born of God do not practice sin.

It’s reasonable to assume that after his conversion, Paul did not instantly understand his new position of being dead to the law and united to Christ (Rom. 7:1-4) or how to walk in dependence on the indwelling Holy Spirit (Rom. 8:4, 13). So I believe that he is describing his own frustrating experience as a new believer, before he learned these truths. And, as I also said, Paul’s main point in the context is to show that God’s law is holy, righteous, and good, but it is not able to deliver us from the power of sin.

As I also explained, I agree that the Christian life is never free from the struggles that Paul describes here. We have to do battle against indwelling sin as long as we live. But Paul is not merely describing a struggle here. Rather, he is talking about a life of consistent defeat. He’s not just describing an ongoing battle, but a losing ongoing battle! I contend that this is not the normal Christian life of a mature believer.